Dispatch of Hope, from Balochistan.

Balochistan is the kind of place everyone has an opinion about.

So much so that the whole province ends up being a figment of everyone’s shared imagination, borrowed from here and there, through other lenses, and through secondhand stories. Today - after many years of holding a second-hand opinion of Balochistan, I saw it up close.

I don’t think there’s any better way to get to know a society better than to visit its schools, because that’s one place where the present can stand at bay because everybody - in one way or the other - is thinking about the future.

There are no two ways about it: we’ve let Balochistan down, so much so that it is heartbreaking to even look at it.

I heard stories today from high school girls who’d forgotten to sing the national anthem because there would be grenade attacks in schools anytime they sang it together in the assembly. I heard from primary-grade Afghan students who’d been called terrorists and from their teachers who’d been dismissed for defending them. I saw the torture of ‘Islamabad’s SNC’ in a school where students speak four different languages: Bruhi, Pashto, Urdu, and Farsi. I heard the stories of coal miners’ children, who’d been left to fend for themselves in a building that seemed worse than the mine their fathers toiled in.

The coal miners’ school.

In Quetta - a few kilometers away from the provincial assembly, I saw a school where 60 girls studied in each class, many of them on floors - without any electricity for the entire school day. In the same school - as I crossed room after room spilling with students, we arrived in a building that looked odd for a school, with white tiles on the floors and walls.

Before I could ask, the teacher told me the new classrooms were in what used to be a clinic adjacent to the school. Forced into a corner, parents and teachers had to pick between health and education - a choice no one should ever have to make.

But it is in these choices that Balochistan shows up.

Pakistan has let Balochistan down. If we are to help, the best place to start is by doing what others haven’t done so far: recognizing their agency despite their challenges and doubling down with them on the choices they are making.

Students on the floors and in corridors in a school in Quetta.

Balochistan’s Invisible Choices

Everywhere I went today, people told me Balochistan was Pakistan’s crown jewel. In various forms, it had been stolen, misplaced, sold, or forgotten.

I know you may find it hard to believe, considering what we’ve read in the news - but Balochistan is not a jewel because of its port, mines, or gas.

It’s a jewel because of its people.

I met teachers today with lesson plans and student profiles and immaculately maintained student data. There’s no state support for this—no Ministry of Education mandate. When I asked an aging teacher how she found time for this, she told me she stayed up till 2 a.m. with her husband, learning how to type it all on an equally aging computer.

A few days earlier - I met the Minister for Education, on whose invitation I’m visiting these schools. Politicians are hard to trust, but Raheela feels different. Her staffers tell me she’s shed tears at the enormity of the task at hand. Before I left for Quetta, she asked me to leave my assumptions at home - and come in the spirit of service. I’m glad I did.

I met another female teacher from Qila Saifullah who had to flee multiple places because of violence, yet somehow completed her Master's and chose to serve in public schools, fighting with parents to let their girls continue schooling beyond puberty. “I know what it means to forge a path,” she told me. “I’m the first in my village to make it this far.”

And perhaps — as if to decisively bury the thought that I’d met with rare outliers, I ended up in Nawab Zada Ismail Ganj in Marri Camp, just outside of Quetta. This is a settlement of the Marris displaced due to the violence in Balochistan. A lone teacher shows up despite almost no infrastructure — you can see for yourself. And that makes all the difference. If someone ever tells you that Pakistan doesn't have greatness in its teachers or that they are only in Islamabad or Lahore, tell them the story of Abdul Rashid Kakar - an oasis in the middle of a desert. Today, at the feet of Professor Kakar, I was schooled in Singaporean pedagogy and the ethical curriculum of Japanese schools, as well as a probable roadmap of decentralized teacher support centers across Balochistan.

No classrooms, no furniture, nor any water or electricity. Yet a great teacher achieving great learning.

One of Kakar’s students - a 6 year old girl reading a 3rd grade textbook.

A short conversation with the great Professor Kakar himself.

Across stuffy classrooms and with secondhand books, in corridors and halls, I saw students struggle to read. But I also saw them keeping at it, with their teachers struggling alongside them. A few years ago, the teachers created a study group, staying back in school, huddled around one tablet to find material online and learn. “That’s when we discovered phonics—and it changed how we saw language,” one of them told me.

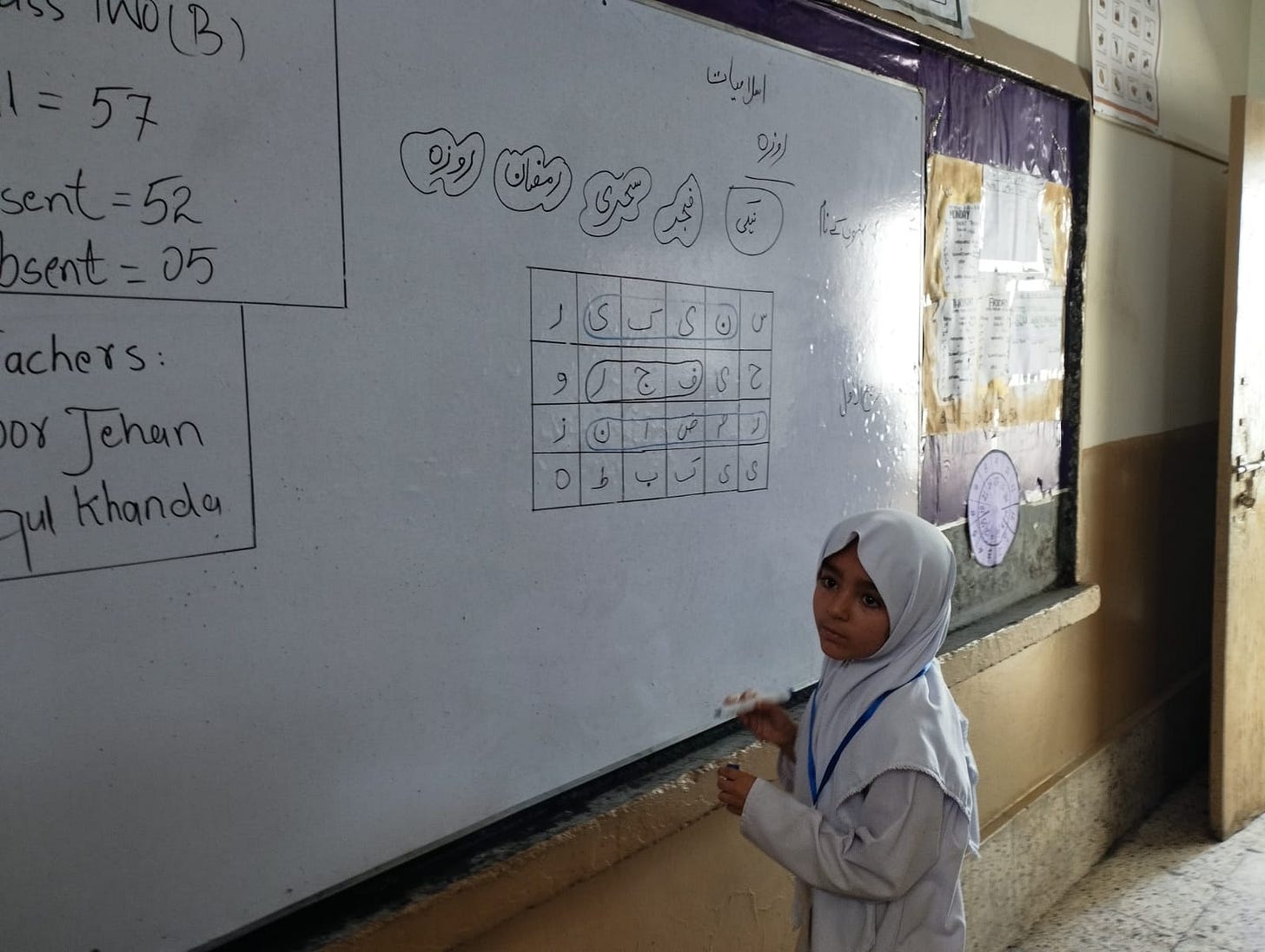

Playing a word puzzle game the teachers picked up online.

I still couldn’t get rid of the thought of having no infrastructure, though. I suppose we all have some biases. Mine is around what we’ve built. How could we support teachers if there weren’t even enough classrooms and electricity?

But there are answers too if you look close enough. In the afternoon I was taken to meet the miraculous Irfan sb - an entrepreneur who’s spent 30 years and built 2000 schools across the entire province. He might have a chance now to secure some of the capital allocated after the education emergency we all saw firsthand. Irfan even has an estimate of what it will take to bring the 3 million OOSC students in Balochistan back to school. $207 million. This seems like a small ask from the $12B or so Pakistan spends on education.

On our choices.

Balochistan’s reminded me of our values; values that might help us as the journey gets harder and the critique louder.

First, there is simply no other way than to stand by teachers. There is no such thing as a permanently good or bad teacher. Only a teacher that we’ve got to serve.

This means that we continue to believe in their best potential—with love that is radical in its nature. We do not hit back when we get hit—we respond with love and understanding. We choose to believe in teachers, especially those who do not yet believe in us.

The second is that our work is much larger than that of technology. We must become the voice for Balochistan (and others) in Islamabad. Their infrastructure challenge is our challenge, their struggle with SNC and language is our struggle. We choose to fight for them even when they aren’t in the room - one for all and all for one.

Our mandate has become immense, but I’ve stopped worrying about how hard it will become. We named our work نیت for a reason—that’s where we’ll start. Eventually, others will walk with us.

And together, we’ll walk toward hard things. Not away from them.

For more information on our work with the government, visit www.niete.pk or find us on LinkedIn/Instagram.